A new book by sociologists explains why organized religions have lost their relevance to streaming new agers and DIY spirituality

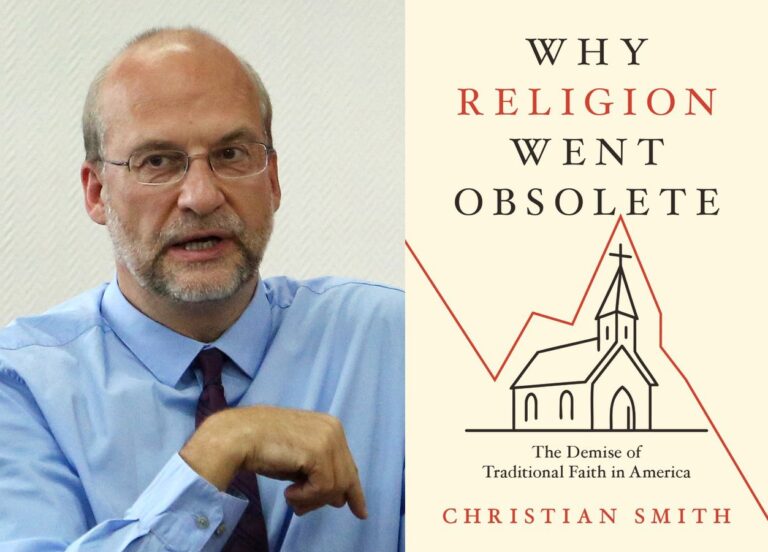

Traditional religion in America, once a cornerstone of public life, may be heading the way of butter churns, lace antimacassars, and wind-up Victrolas—nostalgic artifacts tucked away on the walls of a Cracker Barrel, remembered fondly but no longer functional. So says Christian Smith, a sociologist at the University of Notre Dame, whose new book, The Sacred Project of American Sociology, published by Oxford University Press, maps the quiet unraveling of institutional faith in the United States.

But Smith’s study is not just a dirge for church pews growing cold or offering plates returning empty. It’s a broader cultural diagnosis, and it’s not without hope—or at least fascination. While churches lose members, New Age spiritualities, neopaganism, and “bespoke belief systems” are surging, often facilitated by the same forces that helped unseat traditional religion in the first place.

“We tend to describe religion in terms of ‘decline’ or ‘decay,’” Smith said in a recent interview. “But what’s really happening is more complex—it’s about dislocation. The old frameworks are dissolving because they no longer fit the lives most Americans are living.”

Smith’s book is grounded in more than 200 qualitative interviews conducted across the country and paints a textured portrait of a nation where organized religion hasn’t just lost its grip—it’s lost its grammar. Young Americans, in particular, are turning away not necessarily from belief, but from institutions. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, 42% of Americans aged 18 to 29 identify as “spiritual but not religious”—a category that didn’t even exist in the public imagination a generation ago.

This is not about hostility toward religion, Smith argues. It’s about obsolescence. “DVDs and CDs are still useful to some people,” he said. “I still have a few myself. But most young people stream everything. Religion isn’t being attacked—it’s being outpaced.”

Among the culprits: the rise of radical individualism, digital media that fragments attention and undermines community, and sociopolitical events that have recast religion as either retrograde or politically suspect. Smith points to the post-9/11 suspicion of religious fervor, the disillusionment following the sexual abuse scandals in the Catholic Church, and the rise of high-profile evangelical leaders embroiled in financial or sexual misconduct.

“Even if only a few clergy were involved,” Smith writes, “the contamination effect was enormous. For many Americans, the institution became inseparable from the scandal.”

That’s not to say that Smith considers religion a quaint relic, unworthy of revival. A practicing Catholic and former Presbyterian, he approaches the subject not as a critic, but as a clear-eyed chronicler of deep cultural transition. “There’s no anti-religious agenda in my scholarship,” he insists. “My job is to explain what’s happening, not to cheer it on or lament it.”

One of Smith’s most intriguing insights is that religion’s decline hasn’t created a vacuum—it has catalyzed a shift. In place of organized worship, Americans are experimenting with an eclectic blend of spirituality: astrology apps, energy healing, tarot readings, moon rituals, and “manifestation” culture. These aren’t fringe indulgences; they’re becoming normalized.

“We’re witnessing a restabilization,” Smith said. “It’s just not within the traditional religious framework. It’s outside it—in crystals, in neopaganism, in TikTok spiritual influencers. People didn’t lose their hunger for meaning. They just stopped trusting the usual places to feed it.”

Social forces—delayed marriage, declining birth rates, neoliberal economics, the collapse of shared narratives—didn’t intend to dismantle religion. But they made its traditional forms feel outdated. And while religion’s institutional authority has waned, belief in the supernatural persists. God isn’t gone. He’s just not always in church.

Smith describes the effect on pastors and religious leaders as bittersweet. “One pastor told me he thought his church’s decline was his failure,” he said. “I told him: it’s not just you. Something bigger is happening.”

Ultimately, Smith sees the changes not as a binary shift from religion to secularism, but as a cultural remix. The spiritual landscape is being unbundled and reassembled, shaped by personal experience, algorithmic exposure, and the ambient hum of modern life.

“Religion isn’t dying,” he said. “It’s shape-shifting.”

And maybe, like the best of old vinyl records, it’s waiting to be rediscovered—just not in the same grooves.